Saving Lives: Why Cold Water Immersion is the Gold Standard for Dog Heat Stroke

As proactive pet parents, we strive to give our furry family members the best care possible. When it comes to a life-threatening emergency like heat stroke, having the most accurate, up-to-date information can literally be the difference between life and death. This article will cut through outdated myths and provide you with evidence-based strategies for preventing, recognizing, and immediately treating heat stroke in dogs, emphasizing why cold water immersion is now considered the "gold standard" of care.

What is Heat Stroke in Dogs? A Critical Emergency

Canine heat stroke, or Heat Stroke Injury (HRI), is a severe and rapidly progressing medical emergency. It occurs when a dog's core body temperature rises dangerously high, typically above 104.9°F (40.5°C) and specifically over 105.8°F (41°C), overwhelming their body's natural cooling mechanisms [2, 30]. Unlike humans, who have widespread sweat glands, dogs primarily cool down through panting and limited sweating via their paw pads. This evaporative cooling becomes significantly less efficient in humid environments, especially above 35% humidity [10]. The normal body temperature for a dog ranges from 100.5°F to 102.5°F.

Heat stroke is far more than just being "too hot." This extreme temperature triggers a cascade of systemic dysfunctions, including increased metabolic demand, hypoxia, and circulatory failure [2, 4]. This can lead to inadequate blood flow to vital organs like the gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, liver, and brain, causing direct tissue injury. This damage can then activate Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS), Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC), and ultimately Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome (MODS), which can be fatal [2, 31]. Immediate cooling is crucial to interrupt this destructive cycle and prevent irreversible organ damage.

Causes and Risk Factors: Who's at Risk?

Heat stroke can affect any dog, but certain factors increase susceptibility:

Environmental Exposure: Being left in an unattended car is a leading cause, as car interiors can reach over 120°F (49°C) in minutes on a 75°F (24°C) day [7, 10]. Lack of shade outdoors or overly strenuous exercise in hot or humid conditions are also common triggers [7].

Exercise-Induced: Exercise is the most common trigger for HRI in dogs [9, 14]. It's important to note that heat stroke can occur even in cooler weather or after low-intensity exercise, challenging the common perception that it's only a hot-weather, high-exertion issue [12].

Breed Predisposition:

Brachycephalic (short-muzzle) breeds like Pugs, Bulldogs, and French Bulldogs are at higher risk due to their compromised airways, which hinder efficient panting [5, 11].

Double-coated breeds (e.g., Huskies, Golden Retrievers, Labradors) and giant breeds (due to high body weight) can also be more susceptible [10].

Individual Factors: Older age, obesity, inadequate hydration, a history of previous heat injury, and certain genetic conditions like exercise-induced collapse (EIC) or malignant hyperthermia can significantly increase a dog's risk [3, 9, 10].

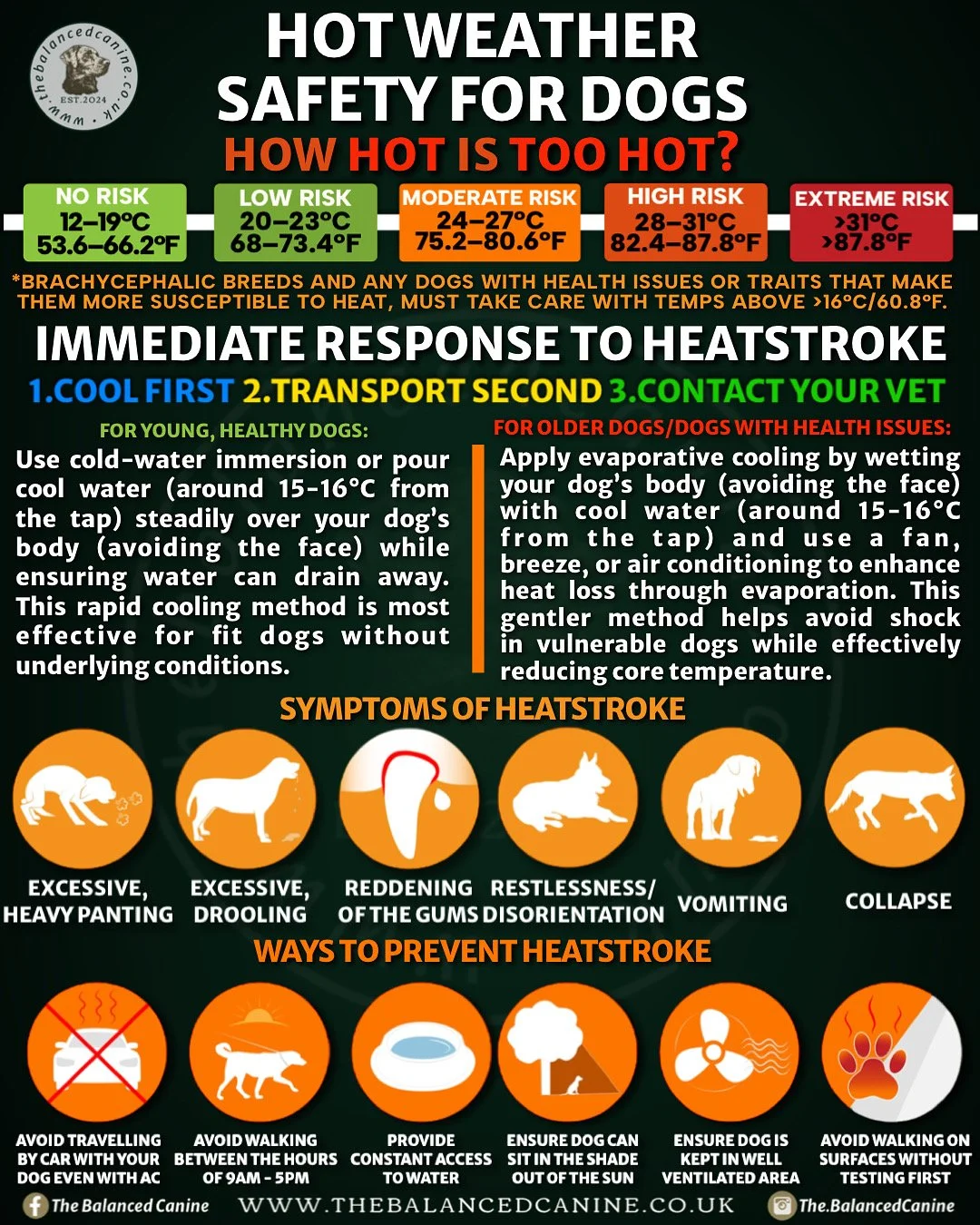

How Hot is Too Hot? Understanding Temperature Risks

While there's no single "safe" temperature for all dogs, general guidelines exist, and individual risk factors must always be considered.

Even healthy Military Working Dogs (MWDs) can transiently reach temperatures over 106°F (41.1°C) during strenuous exercise without immediate adverse effects, but fatal heat stroke has occurred at temperatures as low as 105.8°F (41°C) [6]. This underscores that the ability to dissipate heat is key, not just the temperature itself.

All Dogs (General)

Safe: 60-64°F (15-18°C)

All dogs rely on panting, which is less efficient than human sweating.

Moderate Risk: 70-75°F (21-24°C)

High Risk: 76-80°F (24-27°C)

Heat index (Temp °F + Humidity %) ≥ 150 is unsafe for outdoor exercise.

Dangerous: 81-85°F (27-29°C)

Pavement can be 40-60°F hotter than air temp (e.g., 77°F air = 127°F pavement) [23]. Paws can burn in 60 seconds on hot surfaces.

Brachycephalic Breeds

(Pugs, Bulldogs, Shih Tzus)

Max Working Temp: 18-22°C (64-72°F) [11]

Develop heat stroke faster than other breeds. Shortened airways severely inhibit efficient panting and cooling [11].

Double-Coated Breeds

(Huskies, Malamutes, Golden Retrievers)

High Risk: Above 90°F (32°C)

Struggle in hot weather despite insulation. Thick coats, bred for cold, can trap heat in warm conditions [10].

Large Breeds with Heavy Coats

(Saint Bernards, Newfoundlands)

High Risk: Above 90°F (32°C)

Sensitive to heat due to size and fur. Large body mass combined with dense coats makes heat dissipation difficult [10].

Puppies & Senior Dogs

Increased risk at moderate temperatures (70°F+)

Less ability to regulate body temperature. Young dogs lack developed thermoregulation; old dogs may have Co morbidities [10].

Overweight Dogs

Increased risk at moderate temperatures (70°F+)

Excess body fat impairs heat distribution. Fat acts as insulation, making it harder to cool down [10].

Dogs with Health Issues;

(Cardiac, Respiratory)

Increased risk at moderate temperatures (70°F+)

Pre-existing conditions compromise ability to cope with heat stress. Underlying conditions reduce physiological reserve for thermoregulation [10].

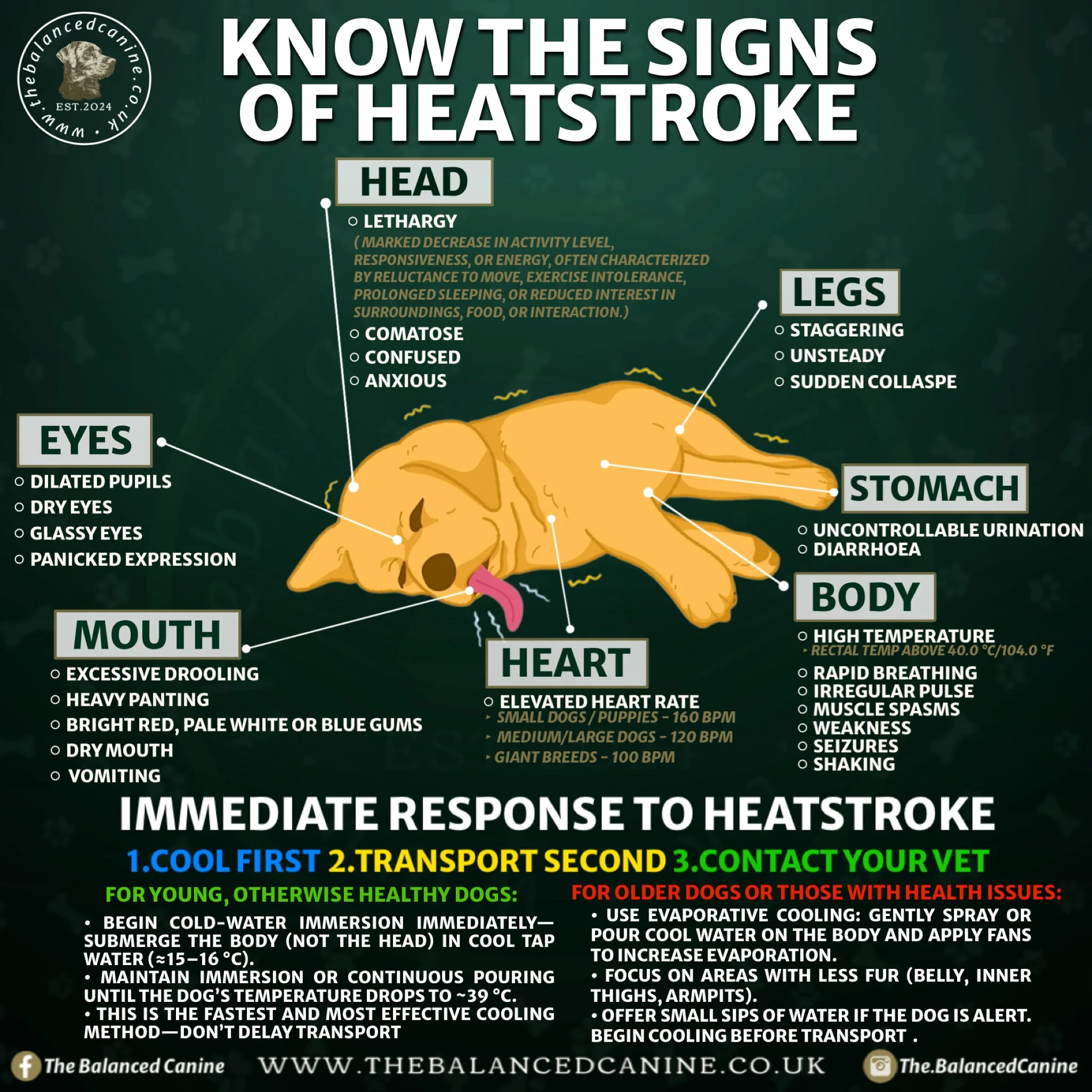

Recognising the Signs of Heat Stroke: Act Fast!

Early recognition is paramount for timely intervention.

Early Signs (Heat Stress/Exhaustion):

Heavy and excessive panting [7]

Profuse drooling [7]

Restlessness or anxiety [7]

Seeking shade or reluctance to move [7]

Bright red or pale gums [7]

Wide, scooping tongue [7]

Progressive Signs (Severe Heat Stroke):

If you observe any of these signs, especially the progressive ones, immediate action is critical.

Immediate Action: "Cool First, Transport Second"

This principle is a critical directive in managing canine heat stroke [9, 13]. The severity of HRI is largely determined by the duration and degree of temperature elevation [2, 31]. Every minute a dog remains hyperthermic, irreversible damage accrues, particularly to heat-sensitive tissues like the brain [9].

By initiating cooling measures before transporting your dog to a veterinary hospital, you can significantly reduce this critical period of elevated temperature, thereby improving their prognosis [9]. Studies show that cooling a pet before hospital arrival can increase survival rates from 50% to 80% [9]. You are the immediate first responder, and your rapid action can directly influence the extent of organ damage and the likelihood of survival.

Debunking the Myth: Cold Water Immersion is Safe and Life-Saving

A dangerous misconception still widely circulated suggests that using cold water or ice water to cool an overheated dog is harmful, potentially causing "shock" or too rapid cooling [19, 21]. This belief often stems from outdated veterinary texts and first aid advice, which theorized that cold water could induce peripheral vasoconstriction, trapping heat in the body's core or triggering cardiovascular collapse [19, 21]. Some historical experimental studies even reported immediate fatalities upon immersion into ice-cold water, leading to recommendations for only "tepid" water [19, 21].

The Scientific Truth: Modern scientific research has unequivocally debunked the "no cold or no ice water" concept [13, 19, 21].

Overwhelming Evidence: Studies consistently confirm that dogs cooled in ice water demonstrate faster cooling without adverse effects compared to those cooled in warmer water [19]. Water immersion is highly effective because it creates a strong thermal gradient, facilitating efficient heat transfer from the dog's skin to the cooler water [22, 26, 27].

Optimal Temperatures: Research on heatstroke dogs shows that tap water (15-16°C or 59-61°F) cools as efficiently as ice water (1-3°C or 34-37°F) in conscious animals [19, 22]. Cooling rates significantly decrease when water temperatures exceed 18°C (64°F) [19]. For comatose dogs, who lose the ability to pant, colder water (1-11°C or 34-52°F) has been shown to achieve faster cooling rates [19].

Real-World Success: A rapid initiation of cooling (within minutes of collapse) using cold (10°C or 50°F) water immersion, continued until the body temperature dropped below 101.8°F (38.8°C), was associated with a 100% survival rate in one study involving over 200 HRI events [13, 19]. Recent field studies involving canicross events observed no adverse effects in dogs cooled with cold-water immersion (0.1–15.0°C or 32-59°F), reinforcing its safety and effectiveness in real-world scenarios [12].

Veterinary Consensus: The current veterinary consensus increasingly endorses Cold Water Immersion (CWI) as a best practice for dogs [19]. The American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA), through its partner VIN, explicitly states that ice-water immersion can quickly cool an overheated pet, acknowledging that this may contradict past advice but represents the latest information applicable to pets [20, 29].

Parallels in Other Species: The Gold Standard Across the Board

The efficacy and safety of cold water immersion are further supported by extensive research in human medicine and other animal fields:

Human Exertional Heat Stroke (EHS): CWI is the established "gold standard" for treating human EHS [16]. Human studies demonstrate that both ice-water immersion (around 5°C or 41°F) and cold-water immersion (around 14°C or 57°F) provide similar, rapid cooling rates, both being significantly more effective than passive cooling methods [25]. EHS is considered 100% survivable if the core temperature is reduced below 40°C (104°F) within 30 minutes, underscoring the critical importance of rapid cooling [16].

Equine Athletes: Direct body application of cold water (sprays or buckets) is the most effective reported method for cooling equine athletes with exertional hyperthermia [16]. The Fédération Équestre Internationale's guidance for equestrian events in high temperatures explicitly recommends water-based cooling methods [16].

Military Working Dogs (MWDs): While some guidelines for MWDs recommend "tepid water (15.6-30°C / 60-86°F)" [6], this can be understood as a pragmatic approach for field conditions where colder water might not be readily available. The overarching message from modern research is that any water colder than the dog, applied aggressively and rapidly, is beneficial, with colder temperatures being more efficient and safe [19].

Addressing the Vasoconstriction and "Shock" Concerns

The historical concern about peripheral vasoconstriction "trapping" heat is largely unfounded [19]. Water has a significantly higher thermal capacity than air (approximately 70-fold greater convective heat transfer) [26]. This immense thermal gradient means that even if some peripheral vasoconstriction occurs, the sheer volume of heat being drawn away from the body by the cold water is so substantial that it overrides any localized heat retention effects. The body's core temperature will rapidly decrease because heat is removed at an accelerated rate [22, 27].

Clinical evidence in both humans and dogs shows that potential side effects like hypothermic overshoot (over-cooling), peripheral vasoconstriction hindering cooling, or cardiogenic shock do not occur when CWI is properly applied and monitored [19]. The danger lies in delaying cooling, not in the temperature of the water.

Table 1: Debunking the Cold Water Immersion Myth: Evidence Summary

Common Concern/Myth

Scientific Rebuttal (Evidence-Based Fact)

Cold water causes peripheral vasoconstriction, trapping heat in the core.

Water's high thermal capacity (approx. 70x air) enables rapid core heat transfer, overriding localized vasoconstriction [19, 26, 27].

Cold water causes "shock" or cardiac arrest.

Studies in humans and dogs show no evidence of adverse effects like cardiac arrest or hypothermic overshoot when properly monitored [19, 24].

Cold water cools too quickly, leading to hypothermia.

Cooling must be monitored continuously and stopped once target temperature (102.5-103°F / 39.2-39.4°C) is reached to prevent iatrogenic hypothermia [9, 15, 19].

Only tepid/lukewarm water should be used.

Cold water (1-16°C) is proven most efficient; tap water (15-16°C) is as effective as ice water for conscious dogs [19, 22]. CWI is the gold standard for humans and endorsed for dogs [16, 19, 20].

Effective Cooling Methods: Your Action Plan

When heat stroke strikes, every second counts. Here's how to cool your dog effectively:

Full/Partial Water Immersion (Cold/Tap Water): The Gold Standard

How: Submerge your dog's trunk and extremities in a bath of cold water or the coldest water available [15, 19]. If using a hose, let it run until the water is cold [19].

Why: This is the most rapid and effective method due to water's high thermal conductivity [19, 22]. Tap water (15-16°C or 59-61°F) is highly effective for conscious dogs [19, 22].

Caution: Always ensure your dog's head remains above water, especially if they are disoriented or unconscious, to prevent drowning [15].

Evaporative Cooling (Water Spray with Air Movement):

How: Mist your dog with water (any temperature colder than the dog) and combine with vigorous air movement from a fan [9, 15].

Why: Effective, often recommended in hospital settings, but generally about half as fast as cold water immersion [9].

Caution: Simply covering a dog with wet towels without air circulation can be counterproductive, acting as an insulator and trapping heat [18, 19]. If wet towels are used, they must be constantly re-wetted and combined with strong air circulation [18].

What NOT to Do:

Do NOT use isopropyl alcohol on paw pads. Studies show it's less efficient than water immersion, can raise heart rate, and may be stressful due to its odor and irritation [24].

Do NOT force water into an unresponsive dog's mouth [15].

Do NOT over-cool your dog. Continuously monitor their temperature (rectal thermometer is best) and stop active cooling once their temperature reaches 102.5-103°F (39.2-39.4°C) [9, 15, 19]. Over-cooling (iatrogenic hypothermia) significantly increases the risk of death [9].

Comparative Cooling Rates: Studies highlight the superior speed of water immersion [17, 28]:

Click here to download and save this graphic to your phone!

Beyond Initial Cooling: Comprehensive Veterinary Management

While your immediate cooling efforts are life-saving, heat stroke is a complex medical emergency requiring professional veterinary care. Many complications may not manifest for hours or even days after the initial event [1]. Your veterinarian will provide intensive critical care, including:

Continuous Monitoring: Of temperature, vital signs, and mental status [1].

Fluid Therapy: Intravenous (IV) fluids are crucial for dehydration, restoring blood volume, and improving tissue perfusion [1, 30].

Managing Complications: Monitoring for and treating potential organ damage (kidneys, liver, GI tract, brain), blood clotting problems (DIC), and cardiac arrhythmias [1, 2, 30].

Supportive Care: Oxygen therapy, electrolyte and glucose management, and medications to protect organs [1, 30].

Owners should be aware that the risk of DIC and organ failure can persist for up to 5-7 days post-event [1].

Prevention is Key: Keeping Your Dog Safe

Preventing heat stroke is always the best approach.

Never Leave Your Dog in a Car: Even with windows open or in the shade, car temperatures rise rapidly and can be fatal [7, 10].

Avoid Strenuous Exercise in Heat: Exercise during the cooler parts of the day (early morning, late evening). Be aware of the temperature ranges for safe walking, especially for at-risk breeds [7, 10].

Provide Shade and Cool Environments: Ensure ample shade outdoors and keep dogs indoors with air conditioning during extreme heat and humidity [7, 10].

Hydration is Vital: Offer frequent opportunities to drink cool water. Hydration helps regulate body temperature and reduces fatigue [7]. There's no definitive research linking drinking cold water to bloat [32].

Acclimatization: Gradually acclimate your dog to heat. Proper acclimatization can take up to 60 days, with partial acclimatization in 10-20 days [6].

General Wellness: Maintain your dog in excellent physical condition and at a healthy weight, as obesity is a significant risk factor [10].

Avoid Muzzling: Do not muzzle your dog during hot weather or exercise, as it interferes with panting [15]. Remove restrictive gear or vests during heat stress [6].

Conclusion: Empowering Pet Parents with Evidence

Canine heat stroke is a severe and potentially fatal condition, but it is treatable. The scientific evidence is clear: rapid, aggressive cooling with cold water immersion is the single most critical factor in improving outcomes for dogs suffering from HRI. The outdated myth that cold water is dangerous has been thoroughly debunked. The true danger lies in delaying effective cooling.

By understanding the causes, recognizing early signs, and implementing proactive prevention strategies, you can significantly reduce your dog's risk. When heat stroke does occur, immediate, aggressive cooling with cold water, followed by prompt veterinary attention, offers your beloved companion the best chance for survival and recovery. Empower yourself with this evidence-based knowledge to keep your dogs safe and healthy.

Want to learn more about different cooking aids to help your dog in the heat? Head to our article linked here.

Sources

1. Canine Heat Stroke - Iowa Veterinary Specialties, https://www.iowaveterinaryspecialties.com/student-scholars/canine-heat-stroke-literature-review

2. Pathophysiology and pathological findings of heatstroke in dogs - PMC - PubMed Central, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7337213/

3. Providing Care for Dogs with Heatstroke - Today's Veterinary Nurse, https://todaysveterinarynurse.com/emergency-medicine-critical-care/providing-care-to-dogs-with-heatstroke/

4. Canine Heatstroke - Israel Journal of Veterinary Medicine, http://ijvm.org.il/sites/default/files/bruchim_2.pdf

5. Heatstroke: A medical emergency | Cornell University College of ..., https://www.vet.cornell.edu/departments-centers-and-institutes/riney-canine-health-center/canine-health-information/heatstroke-medical-emergency

6. K9 Heat Injury CPG, 29 Mar 2025 - Joint Trauma System, https://www.virginiaveterinarycenters.com/blog/summer-safety-series-with-virginia-veterinary-centers-vvc-midlothian-keeping-our-furry-friends-safe

7. Too Hot to Handle: A Guide to Heatstroke in Pets - AAHA, https://www.aaha.org/resources/too-hot-to-handle-a-guide-to-heatstroke-in-pets/

8. Voluntary head dunking after exercise-induced hyperthermia rapidly reduces core body temperature in dogs - AVMA Journals, https://avmajournals.avma.org/view/journals/javma/262/12/javma.24.06.0368.pdf

9. Heatstroke in Dogs | Today's Veterinary Practice, https://todaysveterinarypractice.com/emergency-medicine-critical-care/todays-technician-heatstroke-in-dogs/

10. Heatstroke in Dogs: Signs, Treatment, and Prevention | PetMD, https://www.petmd.com/dog/conditions/systemic/heatstroke-dogs

11. UK Brachycephalic Working Group Consensus Statement: Heat-related illness in dogs, https://www.ukbwg.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/210609-BWG-Position-Statement-Heat-related-illness-in-dogs.pdf

12. Post-exercise management of exertional hyperthermia in dogs participating in dog sport (canicross) events in the UK - ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/378888476_Post-exercise_management_of_exertional_hyperthermia_in_dogs_participating_in_dog_sport_canicross_events_in_the_UK

13. Preventing Canine Heat Stroke: Myths, Facts, and Practical Tips, https://www.northeastk9conditioning.com/blog/heatstroke_myths

14. (PDF) Heat stroke in dogs: Literature review - ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/360403312_Heat_stroke_in_dogs_Literature_review

15. Heat Stroke in Dogs - American Red Cross, https://www.redcross.org/take-a-class/resources/learn-pet-first-aid/dog/heat-stroke

16. Cold Water Immersion: The Gold Standard for Exertional Heatstroke Treatment | Request PDF - ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/6216997_Cold_Water_Immersion_The_Gold_Standard_for_Exertional_Heatstroke_Treatment

17. Voluntary head dunking after exercise-induced hyperthermia rapidly reduces core body temperature in dogs in - AVMA Journals - American Veterinary Medical Association, https://avmajournals.avma.org/view/journals/javma/262/12/javma.24.06.0368.xml

18. Cooling Methods Used to Manage Heat-Related Illness in Dogs Presented to Primary Care Veterinary Practices during 2016–2018 in the UK, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10385239/

19. Are you ready to beat the heat? Cooling hot dogs – more myth busting., https://heatstroke.dog/2024/04/12/are-you-ready-to-beat-the-heat-cooling-hot-dogs-more-myth-busting/

20. Hyperthermia (Heat Stroke): First Aid - Veterinary Partner - VIN, https://veterinarypartner.vin.com/default.aspx?pid=19239&id=4951333

21. Cool, Icy, Cold or Tepid? What's Best for Heat Stroke? - Veterinary Voices UK, https://www.vetvoices.co.uk/post/cool-icy-cold-or-tepid

22. Tap water, an efficient method for cooling heatstroke victims - a model in dogs, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/15782256_Tap_water_an_efficient_method_for_cooling_heatstroke_victims_-_a_model_in_dogs

23. How to Protect Your Dog from Heat Stroke This Summer and What ..., https://www.thequeenzone.com/how-to-protect-your-dog-from-heat-stroke-this-summer-and-what-not-to-do/

24. A Randomized Cross-Over Study Comparing Cooling Methods for Exercise-Induced Hyperthermia in Working Dogs in Training - PMC, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10705156/

25. Ice-Water Immersion and Cold-Water Immersion Provide Similar ..., https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC164337/

26. Physiology of Cold Exposure - Nutritional Needs In Cold And In High-Altitude Environments - NCBI Bookshelf, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK232852/

27. Full article: Mechanism involved of post-exercise cold water immersion: Blood redistribution and increase in energy expenditure during rewarming, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23328940.2024.2303332

28. Comparison of Postexercise Cooling Methods in Working Dogs ..., https://jsomonline.org/product/comparison-of-postexercise-cooling-methods-in-working-dogs/

29. Cooler heads prevail: New research reveals best way to prevent dogs from overheating, https://www.avma.org/news/press-releases/cooler-heads-prevail-new-research-reveals-best-way-prevent-dogs-overheating

30. Heat Stroke in Dogs | VCA Animal Hospitals, https://vcahospitals.com/know-your-pet/heat-stroke-in-dogs

31. Heat stroke in dogs: Literature review - PMC - PubMed Central, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11295878/

32. Summer Safety Series with Virginia Veterinary Centers (VVC) Midlothian: Keeping Our Furry Friends Safe!, https://www.virginiaveterinarycenters.com/blog/summer-safety-series-with-virginia-veterinary-centers-vvc-midlothian-keeping-our-furry-friends-safe